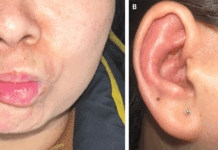

A young 17-year-old Nepali girl was brought to the emergency room with a one-day history of generalized skin rash with mucosal involvement.

Three days prior to the presentation, the patient was started on an oral antibiotic, azithromycin, for sore throat, cough, and fever. On the third day, she started to notice a non-pruritic and painless rash on the trunk which eventually involved the whole body. When she presented, she had extensive (around 20% of the surface area) skin and mucosal involvement, which was painful. Her eyelids and lips were eventually swollen, followed by blistering and crusting.

A clinical diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS-TEN) was made. Azithromycin was stopped but the symptoms didn’t improve. More and more lesions were gradually appearing. After a series of tests, an infective cause of SJS-TEN was suspected, most common being Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Test for mycoplasma IgM was sent which came back positive. All the other tests for infections were negative. CBC revealed high leucocyte and lymphocyte count. Azithromycin was started again with hydrocortisone and the patient improved.

SJS is a rare, dermatological and medical emergency requiring in-patient treatment. It involves the skin and mucosal membranes (oral, genitals and ocular membranes), seen more commonly in children and young adults.

The exact cause why a certain drug or infection elicits SJS is not known, it’s quite unpredictable. The triggering causes may be:

- Drugs: the most common cause of SJS and the most common drugs are anticonvulsants, allopurinol (anti-gout medications), sulfonamides, antipsychotics, antibiotics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. (if taken in the eight weeks prior to symptoms)

- Infections: If the rash is preceded by constitutional symptoms, SJS is classified as infectious, supported by positive serological tests. Common infections leading to SJS include Herpes virus (herpes simplex or herpes zoster), HIV, hepatitis A, Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

When M. pneumoniae-associated mucositis has little or no skin lesions is called atypical SJS or M. pneumoniae-induced rash/mucositis. This is separate from SJS. Since there was mucosal involvement in the case above, the diagnosis is SJS-TEN. The SJS has <10% skin detachment, TEN has >30% and SJS-TEN has 10%–30%.

SJS-TEN presents with signs and symptoms of fever, pain, rash, blistering, purpura, excoriations, mucosal membrane involvement, etc. It may be preceded by certain prodromal symptoms such as malaise, nausea, vomiting, sore throat, arthralgias, and myalgias.

The first step in the treatment is to stop the offending agent or treating the triggering infection. Milder skin lesions may resolve with topical mixtures but extensive skin involvement requires hospitalization especially in the burns unit. Since it has to be treated like a major burn so it’s important to maintain proper hydration and caloric requirement. Keeping the body warm is also essential. Apart from supportive treatment and electrolyte adjustments patients may need corticosteroids, antifungal, and antibiotics to prevent secondary infections. Lesions can be very painful warranting analgesics.

Milder forms of erythema multiforme may only take up to three weeks to resolve but Stevens-Johnson syndrome requires two to three months.

References:

A Case Study of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome-Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SJS-TEN) Overlap in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. (2019, May 30). Retrieved from Hindawi: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criid/2019/5471765/#references

Smelik M. (2002). Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: A Case Study. The Permanente Journal, 6(1), 29–31.

M. Mockenhaupt, C. Viboud, A. Dunant et al., “Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR-study,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 35–44, 2008.