The case above is of a 59-year-old hypertensive man who was brought to the emergency room stable but with an endotracheal tube inserted. This happened after he was found unconscious at home during Crohn’s disease treatment. He had a central venous catheter inserted for intermittent treatment with infliximab for long. Previous attempts to control Crohn’s disease with sulfasalazine, glucocorticoids, and immunomodulatory therapies had been unsuccessful, therefore, infliximab was started parenterally. Physical examination revealed cyanosis of the head, neck, upper trunk, and both arms. Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) was suspected, therefore venography was performed, which showed occlusion of the superior vena cava. Hence the diagnosis was confirmed.

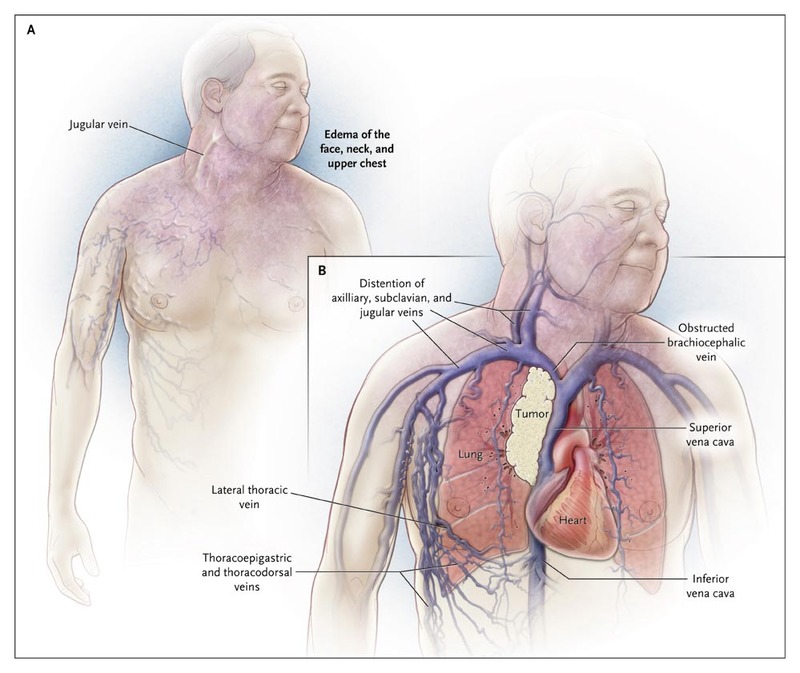

The SVC, lying in the middle mediastinum, is a thin-walled, low-pressure, compressible but major vein of the upper body. Complete obstruction of SCV can lead to SVCS, which is a medical emergency.

Most cases of the SVCS are attributable to mediastinal malignancies, the most common being the bronchogenic carcinoma. Non-malignant causes include infections, benign tumours, fibrosis, aortic aneurysm, atrial myxoma, thrombosis secondary to central venous catheters, etc.

In the case above, thrombosis secondary to the central venous catheter is the culprit behind obstruction of blood flow through SVC. Partial obstruction of SVC may be overlooked or may remain asymptomatic, but as it progresses to the major blockade, symptoms show up, out of which dyspnea is the most common. Other clinical features may include swelling of the face, head and arms, compressive symptoms like dysphagia, hoarseness, shortness of breath, etc., cough, chest pain, visual problems due to congestion of vessels, pleural effusions, orthopnea, distorted vision, papilledema, nasal stuffiness, nausea, light-headedness, and even coma.

Diagnosis is obvious on physical examination in cases with overt SVCS. Milder symptoms suggestive of SVCS may require imaging studies for definitive diagnosis, such as

Chest Xray may reveal a mediastinal mass or widened mediastinum.

Chest CT scan is the initial investigation of choice. It precisely locates the obstruction and may aid in biopsy using a mediastinoscope, bronchoscope, or via percutaneous fine-needle aspiration. Involvement or obstruction of the mediastinal structures like bronchi, oesophagus, etc may also be evident on CT scan.

MRI might have some advantages over CT in providing different views of the images along with the direct visualization of blood flow. When stenting is being considered, MRI would be a better choice as it avoids the contrast medium.

Venography is an invasive but diagnostic procedure, as it effectively pinpoints the aetiology of obstruction, essentially prior to surgical management of the obstructed SVC.

Treatment options depend upon the severity.

Supportive measures like the elevation of the head, supplemental oxygen, corticosteroids, and diuretics are given to alleviate laryngeal or cerebral oedema, whereas radiotherapy and bypass surgeries are the standard and palliative treatments, respectively. Stenting can be considered in an emergency or when the aetiology is undetermined. Anticoagulants and thrombolytics may be given as prolonged conservative treatment

The patient in the discussion here, underwent ultrasound-accelerated

thrombolysis along with bare-metal stenting of the SVC, to relieve the

obstruction.

The patient gradually recovered over a period of two weeks in the hospital with

residual visual impairment in the right eye (20/200). , but prolonged

congestion of the retinal veins resulted in residual visual impairment.