Case Presentation

A 5-year-old Caucasian boy, weighing 19 kg with no significant medical history presented with a complaint of pain in his upper abdomen. The pain he felt was mild in intensity. However, the nature of the pain was deep and was not related to his meals. He experienced it every 2-3 days. Moreover, the pain lasted for only a few minutes at a time, before going away on its own. He was not on any medication and had no previous surgery or interventions. There was no relevant family or psychosocial history. Doctors performed a complete physical examination, which revealed no abnormalities. Moreover, there was no tenderness, masses, or abnormal bowel sounds in his abdomen.

Investigation: Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

The doctors took the boy for an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to investigate his abdominal pain. He had not consumed anything for 10 hours before the procedure. But he appeared anxious, so the doctors gave him 10 mg of oral midazolam, which is an anxiety-reducing medication. The dose of midazolam was 0.52 mg/kg, and the total volume was 5 ml. 45 minutes after the administration of the medication, he became calm, and they took for the procedure.

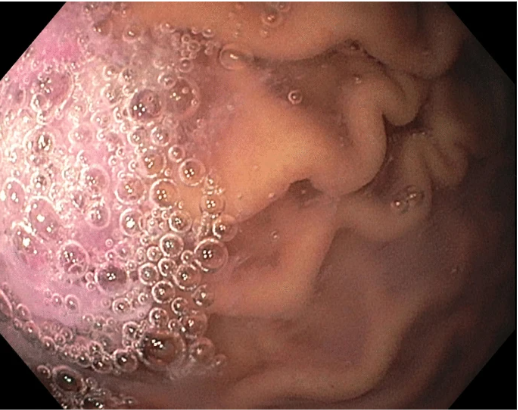

During the induction of anaesthesia, the child appeared drowsy but was still able to answer some questions. This indicated a Ramsay sedation score of 2. The child remained calm throughout the procedure, receiving a Propofol infusion to maintain anaesthesia. The doctors inserted an endoscope into the stomach, where they noted a significant volume of midazolam (pink in colour). The liquid they suctioned from the stomach was identical to the oral midazolam mixture.

After the procedure, the doctors transported him to the recovery room. On arrival, the child was still sedated and only responded to stimulation by jaw thrust, indicating a Ramsay sedation score of 5. The doctors monitored the child’s cardiorespiratory function after the endoscopy. Approximately 40 minutes after arrival in the recovery room, the boy awoke from the effects of anaesthesia. He was calm, awake, and fully oriented.

The doctors performed several gastrointestinal investigations, including a gastric emptying study, and an abdominal ultrasound exam. These were both normal. The child’s pain resolved approximately 2 months later and did not recur on follow-up visits.

Midazolam: The Medication Before Anesthesia

Midazolam can have potential adverse effects, such as respiratory depression, airway obstruction, and delayed recovery from the recovery room. Oral midazolam takes 1-1.5 hours to peak in the serum and has an elimination half-life of almost 4 hours. Its oral bioavailability varies from 21% to 66%, which means that a significant amount of medication may remain unabsorbed in the stomach. However, despite having a small amount of midazolam absorbed, the child exhibited a significant level of sedation.

When doctors give oral midazolam to children, it’s often difficult to interpret how much has been absorbed and how much remains in the stomach. Doctors may think that the leftover midazolam in the stomach will still get absorbed, but this case shows that a child can have a lot of medication left in their stomach even if they seem sedated.

It is essential to consider this issue, particularly in the case of a child who has unexpectedly prolonged emergence from anaesthesia or remains drowsy for a prolonged in the postoperative recovery room. Continued absorption of midazolam provides no desired clinical benefit during the procedure or postoperative period. However, it increases the likelihood that the child will experience adverse effects. Therefore, awareness of this issue is crucial, and further clinical studies are necessary before assuming that this occurs in all pediatric patients.

Conclusion: Effects of Midazolam

In conclusion, while administering oral midazolam to children can be beneficial, it is crucial to consider the potential risks and side effects. This case demonstrates that a significant volume of unabsorbed medication may remain in the stomach, despite having the desired clinical effects. Doctors should be aware of this issue and monitor children carefully, particularly in the postoperative period, to ensure their safety and well-being. Further research is necessary to determine the best management plan for unabsorbed medication in the stomach.