A 55-Year-Old Man Presenting with Recurrent Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Twelve years after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation, a 55-year-old man presented with recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding episodes. This study did not require approval from the Institutional Review Board. Before publishing this case report, including images, the patient provided informed consent. In 2019, the patient was transferred from another hospital to ours due to gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown origin, weakness, and a Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infection. Tacrolimus, prednisolone, and azathioprine were the mainstays of immunosuppression at the time. At the previous facility, an actively bleeding ulcer at the duodenojejunal anastomosis was discovered, which could not be stopped with Histoacryl injection. The patient had a history of stroke and coronary artery disease and had received a simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant in 2007 due to type 1 diabetes with end-stage renal disease.

Case study: recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding due to a stricture of the portal vein anastomotic site

Prior to transplantation, dialysis began at the age of 42 and lasted 1.5 years. The pancreas graft was connected to the recipient common iliac artery via arterial anastomosis of a donor-iliac artery graft, portal vein anastomosis to the inferior vena cava, and enteric exocrine drainage via side-to-side duodeno-jejunostomy. Following surgery, the course was straightforward, with primary graft function. Induction therapy for immunosuppression included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone, and anti-thymocyte globulin. During the follow-up period, no rejection or infection episodes were observed.

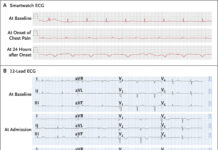

After transferring the patient to our facility due to recurring haemorrhages, the pancreas graft functioned normally, with euglycemia (C-peptide 7.9 ng/ml). Due to a concurrent urinary tract infection, the renal allograft function was initially impaired (serum creatinine 2.1 mg/dl). Renal function returned to normal after anti-infective therapy with imipenem. As the gastrointestinal bleeding continued, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, which revealed an ulcer at the jejuno-duodenal anastomosis with no signs of bleeding but varicose vessels in the same area. CT angiography revealed no suspicious arterial or venous vessels, as well as no signs of abdominal bleeding.

Pantoprazole therapy was started. Multiple RBC transfusions were used to treat recurring low haemoglobin values (haemoglobin 7.0 g/dl). Further tests, such as a repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy, including double-balloon endoscopy, colonoscopy, and capsule endoscopy, were all negative for another acute bleeding focus during the clinical course. A bone marrow biopsy performed for low peripheral leucocyte counts revealed no abnormalities.

Furthermore, the patient experienced recurrent septic episodes with impaired renal function.

Thus, immunosuppressive medication was reduced and temporarily discontinued during episodes of severe infections, especially because the CD4-positive T lymphocyte count (196/l) was low, indicating immunodeficiency at the time; low-dose hydrocortisone treatment was given instead of prednisolone to prevent adrenal insufficiency in a long-term steroid-treated patient. Throughout the complicated course, liver function was compromised by elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase. An abdominal ultrasound revealed no evidence of cirrhosis. A new positive finding of hepatitis E infection with high viral loads concomitant with ascites and CMV reactivation in the blood complicated the recurrent haemorrhage.

The patient’s health was deteriorating, and he developed hemorrhagic shock two months after admission. Another EGD was performed during the hemorrhagic shock, jejunal varices were clipped, and an adrenalin injection was given, but the haemorrhage could not be stopped. A new CT scan revealed a stenosis of the porto-caval anastomosis, necessitating a venous angiography through the right superior femoral vein (5F sidewinder catheter). A balloon catheter (840 mm) was used to dilate the stenosis at the location of the anastomosis between the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the portal vein of the pancreas graft. The possibility of a vena cava narrowing was ruled out. A CT scan a few days later revealed that the stenosis had improved partially.

The perfusion of the abdominal organs, such as the grafted liver and pancreas, was unremarkable.

However, the patient’s need for erythrocyte transfusions persisted, and he had recurring low haemoglobin levels during acute bleeding episodes. There were no cardiovascular adverse events during the entire period, and echocardiography confirmed normal ejection fraction and normal heart chambers.

After 3 months of recurrent bleeding, a surgical intervention was performed, involving an end-to-side anastomosis of the pancreatic graft’s splenic vein at the tail of the pancreatic graft with the recipient’s right iliac vein (analogous to a splenorenal shunt in portal hypertension). The pancreas graft appeared unremarkable macroscopically during surgery. There were few adhesions found. There were tortuous collateral vessels between the donor’s duodenum and the adjacent parts of the intestine.

For the new anastomosis, the right internal iliac vein was mobilised antero-laterally. The anastomosis was patent after performing the new anastomosis between the splenic vein and internal iliac vein with a bovine patch for extension, and it appeared that decompression of the splenic and portal veins of the pancreas graft had been accomplished. A retrograde perfusion of the splenic vein with a diameter of 3 to 4 millimetres was confirmed using colour-coded duplex ultrasound. Thus, it appeared that the decompression of the pancreatic graft’s venous outflow caused by late stenosis of the portocaval anastomosis had been relieved. Unfortunately, due to low haemoglobin levels, blood transfusions were still required.

After 10 more days in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), the decision for graft pancreatectomy was made to save the kidney transplant, based on the clinical course with the aforementioned interventions and uncontrollable recurring bleeding.

The donor pancreas and a portion of the small intestine were removed. There were no complications during the pancreatectomy. In addition to the chronic inflammation of the resected tissues, vessels of the larger lumina were found histologically as evidence of the intestinal tortuous collateral vessels. After transfusing more than 70 units of RBCs during the hospitalisation, the bleeding was finally stopped.

Throughout the 5-month follow-up period following pancreatic allograft removal, no additional blood products were required. The patient’s health improved overall. Hepatitis E infection was no longer detectable. Ganciclovir successfully treated CMV reactivation, and the CD4 T cell count returned to near normal levels. After 3 months of no immunosuppressive medication, a tacrolimus and prednisolone regimen was restarted to provide adequate immunosuppression for the renal allograft, which was still in-situ and functioning well, with a serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dl. A single-antigen bead assay revealed no donor-specific human leukocyte antigen-antibodies. The patient was discharged in good health after 180 days in the hospital. Over the course of a year, the patient’s health and kidney function have remained stable.

Source: American Journal of Case Reports