Colonic Necrosis

The ion-exchange resin sodium or calcium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate or analogue) is commonly used to treat hyperkalaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. It has been linked to digestive issues such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Although uncommon, colonic necrosis and perforation are serious side effects of the medication. We present a case of calcium polystyrene sulfonate-induced colonic necrosis and perforation in this case report to remind clinicians of this uncommon but dangerous toxicity associated with this commonly used medication. This article describes the case of colonic necrosis in a 58-year-old woman who was admitted with bloody stools because of a kidney injury.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate can also bind intraluminal calcium, which can cause constipation, faecal impaction, and bowel obstruction or perforation. The true incidence of colonic necrosis following Kayexalate is unknown. Gerstman et al. reported a 0.27% overall incidence, with a higher postoperative incidence (1.8%). Lillemoe et al. first described colonic necrosis caused by Kayexalate-sorbitol enemas, along with experimental evidence that the necrosis was caused by sorbitol rather than Kayexalate in the presence of uraemia. In both the uraemic and non-uraemic groups, rats receiving sorbitol or Kayexalate in sorbitol enemas developed extensive transmural necrosis.

Case study

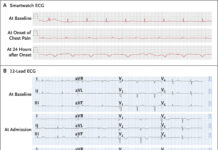

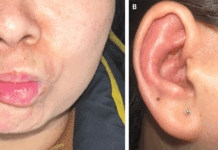

A 58-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with sudden onset bloody stools due to acute-on-chronic kidney injury. She had hyperkalemia at the time of admission, and calcium polystyrene sulfonate — a cation-exchange resin that binds potassium in the colon — had been given multiple times per day for the first six days of her hospitalisation. On hospital day 6, a large volume of painless hematochezia developed, as did a significant decrease in haemoglobin level. A colonoscopy revealed an ulcer that ran from the splenic flexure to the rectum (Panel A).

There was no evidence of active bleeding. In a necroinflammatory setting, a biopsy of the colonic mucosa revealed epithelial injury and basophilic calcium polystyrene sulfonate crystals (Panel B). Calcium polystyrene sulfonate-related colonic necrosis was diagnosed. In rare cases, calcium polystyrene sulfonate or its analogue, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, can cause gastrointestinal injury. The precise frequency and mechanism are unknown. The colon is the most commonly affected site. The patient’s hematochezia improved after the culprit medication was discontinued and bowel rest was implemented. On hospital day 45, she was discharged with improved renal function and a normal potassium level.

It is unknown what caused the necrosis and perforation. Elevated renin levels, which are common in renal insufficiency, may predispose the patient to non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia through angiotensin-mediated vasoconstriction. One gramme of Kayexalate has a theoretical in vitro potassium exchange capacity of 2-3.1 mEq and an in vivo capacity of 1 mEq. According to Emmett et al., in vivo potassium-binding capacity may be lower than previously estimated, ranging from 0.4 to 0.8 mEq/g of Kayexalate resin. Colonic perforation, in contrast to other minor digestive complications associated with Kayexalate treatment, causes significant morbidity and mortality.

As a result, potassium exchange resins may, though infrequently, cause a colonic perforation, and this diagnosis should be considered in a patient treated for acute abdomen. Clinicians must be aware of the rare but serious complications associated with potassium exchange resins.

Source: NEJM