Embolism caused by a simultaneous retrograde venous and anterograde arterial bullet

When a bullet enters the human body, one of two things happens. It either travels through the body in a straight line and exits the other side, or it dissipates its kinetic energy and stops inside the soft tissues. The bullet may occasionally penetrate the wall of an arterial or venous vessel and enter the vascular system. There are two options: retrieval (via open surgery or endovascular intervention) or observation. Surgical intervention has been a standard therapy since its discovery in 1917. In this case, a male patient was diagnosed with an embolism caused by a simultaneous retrograde venous and anterograde arterial bullet.

Case presentation: arterial bullet embolism

This article describes the case of a 30-year-old Iranian (Middle Eastern) male who was previously in a relatively healthy state with no significant medical history or addiction. He was transferred to the emergency department with two close-range shotgun injuries to both buttocks (1 m). The patient was alert (GSC 15) and had vital signs of blood pressure 100/70, respiratory rate 20, temperature 36.7 °C, and oxygen saturation 96%. On examination, his left limb’s distal pulse could not be detected and was cold, with a hematoma at the injury site. Color Doppler sonography of the lower limbs revealed low arterial flow in the distal arteries. Fast abdominal sonography did not show any significant findings. The right buttocks injury was minor, resulting in only mild bruising and hematoma.

The patient was scheduled for surgery

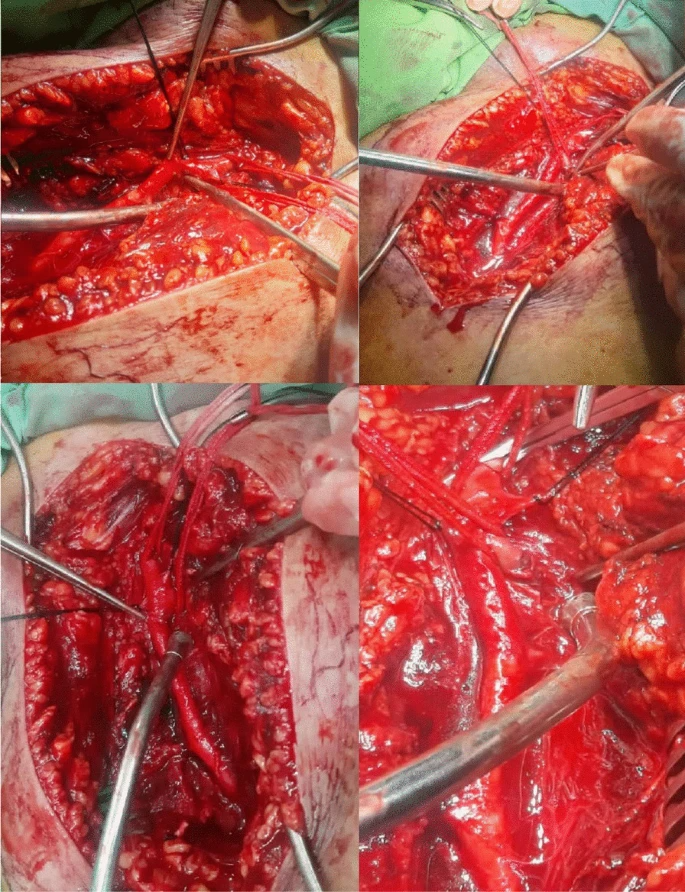

He was given pethidine for pain, 1 g cephazolin for infection prevention, and 2 L normal saline for hydration due to low blood pressure. Following an initial laboratory evaluation that revealed low haemoglobin levels (10 g/dl), he was given two bags of packed cells and a platelet count of 107,000. Coagulation tests came back normal. The patient was scheduled to have surgery. The bullets cut off the origin of the deep femoral origin and the femoral vein on the left side, resulting in avulsion of the proximal end of the left deep femoral artery and partial tearing of the proximal left superficial femoral artery (SFA) (intimal injury).

The deep femoral artery was ligated with silk 2-0, and the great saphenous vein of the right thigh was harvested and dilated. Following systemic heparin infusion, the injured part of the SFA was excised, and the proximal and distal parts of the SFA as well as the popliteal artery were catheterized with Fogarty 4F, followed by thrombectomy with the Fogarty. The bullet was observed to have entered the SFA and travelled to the popliteal deep peroneal trifurcation. A digital angiography of the left lower extremity was performed, revealing a patent trifurcation of the posterior tibialis, anterior tibialis, and peroneal artery. There were no external signs of injury in the popliteal area.

There were no external signs of injury in the popliteal area. Following that, an interposition graft with the great saphenous vein was performed in a continuous fashion with proximal and distal anastomoses made with Prolene 5-0. The flow in the limb was restarted, hemostasis was achieved, and a hemovac drain was inserted. The wound was repaired in layers with Vicryl 2-0 and Nylon 2-0, and a dressing and a long leg slab were applied.

The patient was stable after the procedure

The patient was stable after the operation, with a hematoma in the left groyne. When the patient’s chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) scans were reviewed, it was discovered that one of the pellets (3 mm 5 mm) had travelled to the heart (branch of the right pulmonary artery), most likely via the left femoral vein, causing a local hematoma. With an ejection fraction of 60% and no signs of foreign objects in the heart, the echocardiography evaluation was unremarkable. The patient was discharged in good condition after consulting with a cardiothoracic surgeon, with no cardiovascular complications during his follow-up. The patient was relatively well for the first year after surgery, with no further complications or complaints.

During the patient’s follow-up, a chest X-ray was requested, which revealed no differences from the postoperative image. The patient is now in his 18th month of follow-up, with the gluteal wounds healed and a therapeutic dose of rivaroxaban (20 mg/day) being administered with no further complications or changes in particle positioning.

Source: Journal of Medical Case Reports