Have you ever played

with a doll whose head is attached with a coiled spring to the body?

A slight touch or movement of the doll, makes the head wobble!

The heavy head and the spring together are responsible for its wobbling.

But what causes the head bobbling or wobbling or nodding in children? Children aren’t dolls; they don’t have heads attached with springs, then why the head bobbles? Is it intentional?

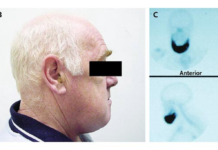

A 5-year-old girl presented to the pediatric neurosurgery clinic with excessive, repetitive head nodding for the past 2 years.

On examination, anteroposterior head-bobbing movements were observed, which were continuous and rhythmic, at a frequency of 2 to 3 Hz. Otherwise, the girl was alert with normal cognitive function.

Her head movements reduced in intensity substantially when she started talking, which showed that the volitional activities diminish the head bobbling.

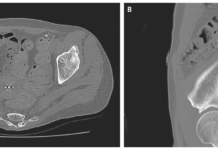

A distinct, thin-walled, suprasellar cystic lesion was seen on magnetic resonance imaging of the head (Panel A, arrow). The ventriculomegaly (Panel B) seen on the MRI was due to the obstruction of the foramina of Monro or the third ventricle due to the lesion.

A diagnosis of a suprasellar arachnoid cyst with bobblehead-doll syndrome was made.

Endoscopic cystoventriculostomy and cystocisternostomy for the suprasellar arachnoid cyst were performed. The head movements’ frequency and severity had reduced in the first 6 weeks after the procedure.

Bobblehead-doll syndrome is a rare movement disorder exclusively found in children with a mean age of 3 years. It is associated with third ventricular cystic abnormalities or lesions. Suprasellar arachnoid cysts, and third ventricular tumors being the two most common associations.

The disease’s name is justified as it is characterized by repetitive, involuntary, to and fro head-nodding in the anterior-posterior axis (yes-yes) or the lateral direction (no-no), either continuous or episodic. These wobbling head movements can be due to compression and distortion of the red nucleus, medial thalamus, and dentatorubrothalamic pathways.

Some proved the movements to be a display of ‘learned behavior’ as the movements apparently aid in temporarily relieving the obstruction at the foramina of Monro, thus partially alleviating the symptoms.

The recorded frequency of the head movements is usually between 2 to 3 Hz. Patients do not display these head movements during sleep. Also, during volitional activities, the movements temporarily disappear or attenuate, indicating a possible role of basal ganglia. However, these movements are highly sensitive to sensory stimuli.

The clinical presentation varies according to the severity of the underlying lesion. The clinical features may include macrocephaly, ataxia, learning problems, developmental delay, impaired cognition, tremors, hyperreflexia, headache, visual disturbances, hypertonicity, weakness, vomiting, etc.

The best investigation modality in such cases is the mid-sagittal magnetic resonance imaging to delineate the soft tissue and the flow of cerebrospinal fluid.

Image Source: NCBI

BHDS may not always require treatment. It can be closely followed with an annual MRI when the symptoms are mild, and the underlying lesion is stable. When necessary, the management approach is decided on an individual basis, including, endoscopic fenestration, endoscopic ventriculocystocisternostomy, and cystoventriculoperitoneal (CVP) shunt.

References:

Nitish Agarwal, M. B. (2019, January 31). Bobblehead-Doll Syndrome. Retrieved from The New England Journal of Medicine: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm1808747

Reddy OJ, Gafoor JA, Suresh B, Prasad PO. Bobblehead doll syndrome: A rare case report. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2014;9(2):175‐177. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.139350