Case Presentation

At 11 weeks of gestation, a 39-year-old African woman, Gravida 6, presented with severe lower abdominal pain. It had progressively increased over the past 4 hours. The pain, characterized as sharp and continuous, was accompanied by dizziness, but there was no reported vaginal bleeding. Notably, the patient had a history of four previous hysterotomy scars, resulting in only one living child. She had experienced uterine ruptures in 2016 and 2019 at 34 and 28 weeks, respectively.

A review of her obstetric history revealed significant complications. In 2013, her first pregnancy resulted in an emergency cesarean section at 28 weeks due to non-reassuring fetal status, followed by a neonatal death. The second pregnancy in 2015 led to an emergency cesarean section at 31 weeks and subsequent neonatal death. The third pregnancy in 2016 involved preeclampsia, which led to delivery at 36 weeks via emergency cesarean section due to uterine rupture, with a good neonatal outcome. In 2018, her fourth pregnancy ended in an incomplete miscarriage in the first trimester, which the doctors medically managed. The fifth pregnancy in 2019 resulted in a uterine rupture and stillbirth at 28 weeks of gestation.

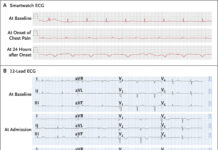

Investigations

Antenatally, the patient tested positive for antiphospholipid syndrome and initiated a daily regimen of subcutaneous enoxaparin (40 U) and acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) (150 mg). Various antenatal assessments, including the dating scan and nuchal translucency, yielded normal results.

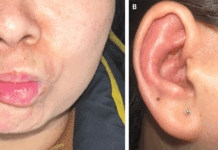

Upon admission, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a blood pressure of 110/67 mmHg and a pulse rate of 89 beats per minute. The oxygen saturation was at 100%, the respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and the temperature was 36.8 °C. Clinical examination revealed mild conjunctival pallor and abdominal assessment indicated a fundal height corresponding to a 15-week gestation. She also had severe tenderness and guarding.

The doctors observed the patient closely, considering her complex obstetric history and the potential risks associated with her current condition. Doctors performed further diagnostic evaluations and interventions to address the acute presentation and manage potential complications. The interdisciplinary approach aimed to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes.

The patient’s complete blood count revealed a haemoglobin level of 11.2 g/dl, a platelet count of 226 cells/µl, and a white blood cell count of 15.29 cells/µl.

Management

Upon conducting a focused abdominal sonogram of trauma (FAST) ultrasound, doctors found free fluid in the abdomen alongside a viable intrauterine pregnancy. In response to this finding, the patient provided consent for an urgent diagnostic laparoscopy. Doctors promptly took her to the operating theatre.

During the laparoscopy, doctors discovered an approximately 10 cm anterior uterine rupture, accompanied by a hemoperitoneum of approximately 1000 ml. Given the early nature of the uterine scar, doctors decided to convert it to an open procedure to facilitate a more effective uterine repair. They converted the surgery to an open procedure, revealing the gestational sac protruding from the uterus. Subsequently, the placenta, attached to the posterior uterine wall, was expelled. The three-layered repair of the uterine rupture was carried out using a polyglactin (vicryl) number 0 suture, achieving hemostasis. The abdomen underwent irrigation with normal saline, followed by closure in layers. The entire procedure transpired without intraoperative complications. The patient recovered well, and doctors discharged him on the third postoperative day.

This case represents a rare instance of uterine rupture in the first trimester. It has an occurrence with an incidence of approximately 0.3% during term deliveries and is almost unheard of in the first trimester. Uterine rupture poses significant morbidity and mortality risks, with a mortality rate of about 1 in 500 cases of rupture. Roughly 23% of patients experiencing uterine ruptures may require hysterectomy, with a larger proportion requiring transfusion. Timely detection and intervention are crucial to preventing such morbidity and mortality.

Uterine rupture

Uterine rupture is primarily associated with previous uterine scarring from procedures like cesarean section, myomectomy, or hysteroscopic resection of a uterine septum. Most cases of uterine rupture occur during labour, with various predisposing factors identified. These include induction of labour with misoprostol, which carries a uterine rupture risk of 5–10% when used in patients with a previous cesarean delivery. Obstructed labour or labour dystocia at advanced dilation (greater than 7 cm) and a prolonged second stage have also been associated with an increased rupture risk. Other contributing factors include fetal manipulation during delivery, with procedures such as forceps delivery and internal podalic version increasing the risk of rupture. Malpresentation and abnormal placentation, such as the placenta accrete spectrum, have also been implicated in uterine rupture. Iatrogenic causes include instrumentation during the evacuation of a miscarriage.

The clinical presentation of uterine rupture in the first trimester may be nonspecific, potentially leading to a delayed diagnosis. This delay can result in catastrophic bleeding and death. A high index of suspicion is crucial, especially in the presence of acute abdominal pain and unstable vitals. Differential diagnoses include ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, molar pregnancy with molar invasion, or a bleeding corpus luteum.

The diagnosis of uterine rupture in the first trimester can be confirmed through ultrasound imaging. In this case, ultrasound revealed free fluid in the peritoneum with an intrauterine gestation, features commonly observed in sonography for uterine rupture. Other described features include distortion of the uterine wall or the presence of fetal parts outside the uterus. In cases of severe bleeding, ultrasound may have limited value, necessitating urgent diagnostic surgery, which may include laparoscopy, to diagnose and promptly treat the condition.

Management options: Uterine Rupture

Management options for uterine rupture include surgical repair of the tear or hysterectomy if repair fails. Laparotomic repair has been demonstrated to be superior to laparoscopic repair due to better surgeon mobility in performing multilayer repair, improving wound strength, creating better exposure, and achieving quicker hemostasis. However, there is also evidence of laparoscopic repair in the early postpartum period following vaginal birth after a prior cesarean, offering advantages such as quicker recovery time and a smaller surgical wound. Nevertheless, its drawbacks include reduced exposure for the repair and weaker structural integrity compared to laparotomic repair.

The primary complication of uterine rupture in the first trimester is life-threatening maternal haemorrhage, which could lead to hemorrhagic shock, coagulopathy, multiorgan system failure, and death. Uterine rupture accounts for 14% of all hemorrhage-related maternal mortality.

The recurrence risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies is estimated to be 4–33%. Due to this risk, patients are typically advised to undergo a cesarean section in future pregnancies before the onset of labour or immediately at the onset of spontaneous preterm labour.