Case Report

Mucosal melanoma is a malignant tumor that develops from melanocytes in the mucosa. Sinonasal mucosal melanomas make up 1% of all melanomas and roughly 4% of all sinonasal malignancies. There is a large patient age range, with the incidence peaking in the seventh decade of life. There is no sexual preference. Mucosal melanomas are biologically different from cutaneous melanomas. The causes of melanocytosis, for example, are unknown.

Sinonasal mucosal melanomas are most commonly found in the nasal cavity or septum, with a rare occurrence in the nasopharynx or maxillary sinuses. Clinical symptoms include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and facial pain. They are typically detected late due to the presence of vague symptoms that resemble benign illnesses. Locally aggressive and widespread, with bone/orbital involvement. It may also spread to distant organs such as the lungs, liver, brain, and lymph nodes. Immunohistochemical examination is required, especially in amelanotic malignancies. S100 protein and melanocytic markers (HMB45, tyrosinase, melan-A, MITF, and S0X10) have varying sensitivity depending on the morphological type.

S100 protein is found in more than 95% of epithelioid/undifferentiated melanomas and only 85% of spindled mucosal melanomas. Melanocytic markers exhibit similar variety, with 75-80% of melanomas having epithelioid morphology compared to 65-70% of spindle cell melanomas. Depending on the severity of the condition and the type of facility, several treatment regimens might be implemented.

Treatment options include surgical excision, which is typically inadequate due to anatomy, radiation to improve local control, immune checkpoint inhibitors in more advanced cases, and targeted therapy. They have a terrible prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate for 20-45% of the patients due to late identification and metastases.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old African female appeared with a 6-month history of increasing nasal blockage, primarily affecting her left nostril. This was accompanied by repeated epistaxis, which was equally noticeable on the left side. She denied feeling headaches, vision abnormalities, or periods of unconsciousness. On examination, the nose had a black polypoid lesion on the left nostril, forcing the septum on the opposite side, and there was no intraoral bulging.

Investigation

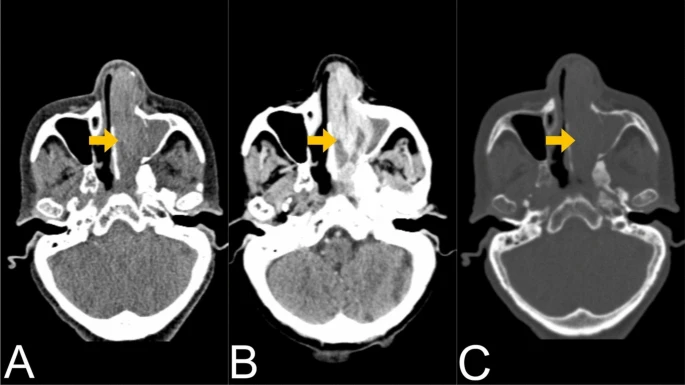

All laboratory examinations were within normal limits. A CT scan of the paranasal sinuses revealed an enhancing soft tissue mass infiltrating the left nasal passage and ethmoid air cells measuring approximately 7.3 × 2.5 × 2.8 cm in size with associated nasal occlusion and obstruction of the ipsilateral osteomeatal complex and sphenoethmoidal recess leading to maxillary and sphenoid sinus opacification. The medial aspect of the inferior orbital wall as well as the left medial maxillary sinus wall were destroyed. Regional lymphadenopathy was not visible. The patient was classified as stage IVA by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

A CT examination of the chest and abdomen showed no distant metastases. The ECG and ECHO results were normal. The patient was set to undergo functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS).

Intraoperatively, a blackish mass in the left nasal cavity blocked the nostrils, extending to the anterior third of the inferior turbinate, septum, middle turbinate, and floor, with mucoid discharges from the maxillary, ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses, along with normal mucosa. The blackish mass was debulked, and a sample was collected for histological examination.

Histopathology identified it as a mucosal melanoma, which was verified by Human Melanin Black (HMB45) immunohistochemistry.

Treatment

The patient had the tumor surgically removed, but due to the severity of the disease and its placement, only debulking was possible. Discussion with the interdisciplinary team: adjuvant immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors was suggested. However, due to accessibility and budgetary difficulties, the patient was unable to continue with the immunotherapy. Instead, they chose the best supportive care with symptomatic control.

Discussion

Mucosal melanoma is a highly aggressive cancer that develops from melanocytes found in mucosal membranes. It accounts for about 1% of all melanomas and has a far poorer prognosis than cutaneous melanoma due to its late diagnosis and aggressive nature. The sinonasal tract is one of the most prevalent areas of involvement in the head and neck, accounting for roughly half of all mucosal melanomas in this region. Unlike cutaneous melanomas, which are linked to ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, the cause of mucosal melanomas is unknown.

Conclusion

Mucosal melanoma of the sinonasal tract is a very aggressive cancer with a dismal prognosis due to late detection and restricted therapeutic options. This example demonstrates the diagnostic and treatment complications connected with this entity. Early detection, multimodal management, and developing systemic medicines provide hope for better outcomes, but more research is required to create more effective treatment regimens.