Paradoxical Kinesia in Parkinson’s Disease: Preserved Cycling Despite Severe Freezing of Gait

Freezing of gait (FOG) is one of the most disabling motor complications of Parkinson’s disease (PD), particularly in advanced stages. It is characterized by brief, episodic inability to initiate or continue walking, often described by patients as feeling as though their feet are “glued to the floor.” FOG is strongly associated with falls, loss of independence, and reduced quality of life. The phenomenon described in this case—a patient with severe freezing of gait who retains the ability to ride a bicycle—represents a striking example of paradoxical kinesia and offers important insights into motor control in Parkinson’s disease.

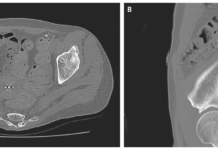

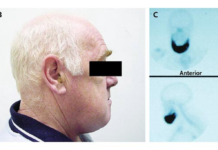

The patient was a 58-year-old man with a 10-year history of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who presented with incapacitating freezing of gait. He experienced extreme difficulty initiating walking and could take only a few short, shuffling steps even when provided with an external visual cue, such as the examiner placing a foot in front of him. Attempts to walk rapidly progressed to forward festination, followed by loss of postural control and a fall. Axial turning was impossible, further highlighting severe impairment of gait automaticity and postural regulation.

In contrast, the patient’s ability to ride a bicycle was remarkably preserved

Once mounted, he could pedal smoothly and maintain balance without difficulty. Notably, freezing of gait reappeared immediately upon dismounting, indicating that the improvement was task-specific rather than a generalized motor benefit. This dissociation between walking and cycling ability is a well-documented but still incompletely understood phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease.

Freezing of gait is believed to result from dysfunction within neural circuits responsible for the automatic execution of learned motor programs. These circuits involve interactions between the basal ganglia, supplementary motor area (SMA), brainstem locomotor centers, and cognitive control networks. In Parkinson’s disease, degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra leads to impaired basal ganglia output, disrupting the internal cueing mechanisms required for smooth gait initiation and continuation. This impairment is particularly evident during situations requiring complex motor planning, such as turning, navigating narrow spaces, or initiating movement from rest.

Paradoxical kinesia refers to the sudden, transient ability of patients with Parkinson’s disease to perform movements that are otherwise severely impaired, often in response to specific external stimuli or emotional contexts. Examples include running from danger, stepping over obstacles, or, as in this case, cycling. Cycling appears to bypass some of the defective neural pathways involved in walking. Unlike gait initiation, which relies heavily on internally generated motor commands, cycling provides continuous, rhythmic, externally driven proprioceptive input. This rhythmicity may facilitate movement by engaging alternative motor networks, including cerebellar and premotor circuits, that are relatively preserved in Parkinson’s disease.

Neuroimaging and neurophysiologic studies suggest that cycling relies less on the supplementary motor area and basal ganglia and more on sensorimotor integration and repetitive pattern generation. The continuous circular motion of pedaling may reduce the need for step-to-step motor planning, which is a key point of failure in freezing of gait. Additionally, the seated position during cycling reduces postural demands, further decreasing reliance on impaired axial motor control.

The inability of the patient to turn axially while walking, contrasted with preserved balance during cycling, underscores the role of postural instability and impaired anticipatory postural adjustments in freezing of gait. Turning requires complex coordination of axial muscles and anticipatory shifts in center of gravity—processes that are heavily dependent on basal ganglia function. Cycling minimizes these requirements, offering a more stable and predictable motor task.

Clinical Findings

Clinically, this phenomenon has important therapeutic implications. Recognition that certain motor activities remain preserved in patients with severe gait freezing has led to the development of targeted rehabilitation strategies. Cycling, both stationary and outdoor, has been explored as a safe and effective form of exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease, even those with advanced freezing of gait. Studies have shown that cycling may improve overall mobility, cardiovascular fitness, and even gait performance, possibly through activity-dependent neuroplasticity.

Moreover, understanding paradoxical kinesia reinforces the importance of external cueing strategies in managing freezing of gait. Visual cues, auditory rhythms, and tactile feedback can partially compensate for impaired internal cueing, although their effectiveness may vary depending on disease severity. The failure of simple visual cues in this patient highlights the advanced nature of his condition and the need for individualized approaches.

In summary, this case illustrates a dramatic dissociation between walking and cycling abilities in advanced Parkinson’s disease, exemplifying paradoxical kinesia. The preserved ability to cycle despite incapacitating freezing of gait underscores the complexity of motor control in Parkinson’s disease and highlights the role of task-specific neural networks. Studying such phenomena not only deepens our understanding of disease pathophysiology but also informs innovative rehabilitative strategies aimed at preserving mobility and independence in affected patients.

References

- Nutt JG, et al. Freezing of gait: Moving forward on a mysterious clinical phenomenon. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(8):734–744.

- Snijders AH, Bloem BR. Images in clinical medicine: Cycling for freezing of gait. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):e46.

- Nieuwboer A, Giladi N. Characterizing freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: Models of an episodic phenomenon. Mov Disord. 2013;28(11):1509–1519.

- Vercruysse S, et al. Freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: Motor, cognitive, and behavioral aspects. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(4):354–364.

- Snijders AH, et al. Cycling skills in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(6):1053–1057.