Case of dietary zinc deficiency-associated dermatitis

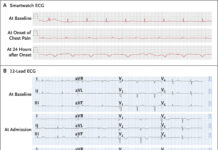

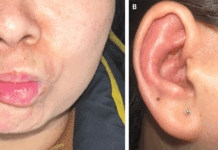

A 2-year-old with an 8-month history of dermatitis, hair loss, and watery diarrhoea was referred to a dermatology clinic. The infant had been breast-fed exclusively until 6 months of age, when a vegetarian solid-food diet of produce and natural grains was introduced. The symptoms began after the child was weaned from breast milk to cow’s milk at the age of 16 months. The child was irritable during the examination; he had angular cheilitis, alopecia, and erosions with crusted borders across the face and scalp, as well as around the mouth, eyes, and ears (Panels A and B). The rash spread to the perianal region, the trunk, and all four limbs. Based on the findings and further tests, the child was diagnosed with dietary zinc deficiency-associated dermatitis.

The serum zinc level was 0.32 g per millilitre (reference range, 0.65 to 1.10), and the alkaline phosphatase level was low. Because zinc is a cofactor for alkaline phosphatase activity, a patient with zinc shortage may have a low alkaline phosphatase level. Dietary zinc deficiency-associated dermatitis was diagnosed. Oral zinc supplementation as well as dietary adjustments were advised. The alopecia and dermatitis had resolved at a 3-week follow-up visit. The symptoms did not return after the zinc treatment was discontinued three months later.

Zinc is a cofactor for metabolism and cell growth

Zinc is a trace element that acts as a cofactor for specific enzymes involved in metabolism and cell growth; zinc promotes immunological function, protein metabolism, gastrointestinal tract development, and genetic processes. Dermatitis around the limbs and bodily orifices, diarrhoea, and reduced immunological function characterise the condition, but chronic zinc deficiency disorder can lead to liver or kidney failure. Acrodermatitis enteropathica, a rare genetic condition, has the same clinical symptoms as acute zinc deficiency disorder but is a zinc absorption metabolic disorder. Zinc is a common component in PN. Premature newborns on PN require 400 g/kg/body weight/day of zinc to maintain serum levels and stimulate growth, whereas full-term infants on PN require 200 g/kg/body weight/day.

Studies have shown that newborns with zinc-deficient PN have lower serum zinc levels

Several studies have found that newborns on zinc-deficient PN had gradually lower serum zinc levels, particularly premature and low birth weight infants. Although zinc deficiency illness can have major health consequences in people of all ages, babies are especially vulnerable since their systemic zinc reserves are not fully established and they rely entirely on breast milk or formula. As a result, the American Society for Clinical Nutrition advocates incorporating injectable zinc into PN for all newborns and children, with a special emphasis on those who are premature, have low birth weight, or have chronic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Zinc deficiency in babies is difficult to detect for a variety of reasons, including vague signs and symptoms. Dermatitis and development impairment are the most typical symptoms of zinc deficiency illness, which can be caused by a variety of factors. Only the most severe individuals have zinc deficiency disorder-associated dermatitis as a physical manifestation. The withdrawal of the amount of blood required to measure the serum zinc level in preterm infants may jeopardise the infant’s health; thus, routine testing is not undertaken, which may explain, in part, why no other cases were documented.

Signs and symptoms

Physicians who administer PN should be aware of the hazards of micronutrient deficit, including zinc insufficiency, in preterm infants who require higher doses or are unable to take necessary quantities. During a scarcity, physicians may need to reserve micronutrients for the most vulnerable individuals. According to FDA, shortages of additional PN micronutrient components (e.g., selenium, chromium, and copper) are also ongoing; FDA is working with producers to prioritise which micronutrients to produce and to explore alternative sources for the micronutrients. Shortages will persist until production of these micronutrients increases. Hospitals with limited stockpiles of injectable zinc might consider conserving available supplies for newborns at highest risk of insufficiency.

Monitoring for signs and symptoms of micronutrient deficiencies is recommended whenever PN without the standard micronutrients is delivered to patients, whether due to shortages or other concerns. When applying these principles to individual clinical care, health-care practitioners should constantly examine the specific clinical condition.

Source: NEJM