Case Presentation

A 69-year-old male farmer from China began experiencing persistent chest pain, accompanied by intermittent coughing, expectoration, and fever. The patient sought medical attention at the respiratory department due to worsening chest pain and cough, along with a low-grade fever of 37.8 °C.

The patient’s medical history included a 10-year battle with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), for which he had been prescribed tripterygium glycosides (20 mg three times per day) and prednisone (10 mg per day) since 2015. Tripterygium glycosides, a traditional Chinese herb, is known for its anti-inflammatory and cellular immunity inhibition effects. However, the patient independently discontinued prednisone due to concerns about potential side effects.

Examination

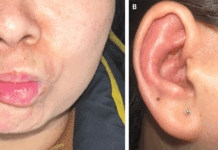

Upon physical examination, coarse breath sounds and wet rales were noted in both lungs. He also had mild oedema in both lower limbs. A palpable lymph node without tenderness was identified in the right axillary, and no organomegaly was detected in the abdomen.

Initial blood tests revealed mild anaemia, a low haemoglobin concentration (98 g/L), and an elevated eosinophil ratio (7.2%). Other blood parameters such as white blood cell count, neutrophil ratio, lymphocyte ratio, and blood platelet count, were within normal ranges. However, elevated levels of C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, immunoglobulin G (IgG), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were observed. Total protein, albumin, and blood glucose levels were below the normal range.

Investigations

Further diagnostic investigations through computed tomography (CT) scans showed diffuse bronchial wall thickening. Moreover, there were patchy areas of air trapping consistent with small airway disease. A colour Doppler ultrasound revealed enlargement of the right axillary lymph node, and a pulmonary function test showed mild small airway obstructive ventilation dysfunction.

Management

Antibiotic treatment initially proved to be ineffective, leading to a lymph node biopsy. The biopsy revealed reactive hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue with plasmacytic hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the clonal proliferation of plasma cells. The patient was ultimately diagnosed with plasma cell type Castleman’s disease (CD), accompanied by bronchiolitis obliterans (BO).

Following successful surgery to remove the enlarged lymph node, adjuvant therapy with glucocorticoids was suggested. However, the patient declined due to concerns about potential side effects. Postoperatively, the patient was administered immunosuppressive medication, including tri pterygium glycosides (20 mg three times per day) and leflunomide (20 mg per day).

Follow-up

The patient remained asymptomatic and continued the prescribed medication regimen. A bronchoscopy performed six months post-surgery revealed no abnormalities. After 11 months of follow-up, pulmonary function tests indicated mild small airway obstructive ventilation dysfunction. Additionally, blood tests showed improvements in C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IgG, and IL-6 levels.

The patient, who has not undergone rheumatoid factor testing, is still under follow-up and maintains a satisfactory quality of life.

Castleman Disease

Castleman disease (CD), a rare lymphoproliferative disorder, encompasses two main types: unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) and multicentric Castleman disease (MCD). The histopathological classification includes hyaline vascular type CD (HV-CD), plasma cell type CD (PC-CD), and mixed type CD.

Despite an increasing number of reported cases, diagnosing CD, particularly when coupled with bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), remains challenging. BO, a rare and severe complication of Castleman disease, significantly impacts prognosis and is a leading cause of mortality. Unfortunately, there is currently no standardized treatment for CD, and its mortality rate is high.

Our report details a case of PC-CD with accompanying BO, initially presenting with respiratory systemic manifestations and misdiagnosed as a pulmonary infection. BO stands out as a crucial prognostic factor and the primary contributor to CD-related fatalities. Early disease detection, prompt tumour resection, and effective adjuvant therapy. This includes glucocorticoids or immunosuppressive medication, which are pivotal in controlling BO progression.

Clinicians play a crucial role in patient education, emphasizing the disease’s course and the importance of regular follow-ups to monitor clinical and laboratory changes. Swift administration of treatment is essential not only for improving patients’ quality of life but also for enhancing their prognosis and reducing mortality rates.

Discussion: Castleman Disease

Understanding the causes of Castleman disease (CD) remains a challenge, with unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) potentially linked to clonal proliferation of tumour stromal cells and acquired gene mutations. The primary cell source in UCD is likely follicular dendritic cells. In multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), immune dysfunction and increased cytokine levels due to factors like IL-6, human herpes virus-8 (HHV-8), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) play a role. The predominant pathological types in UCD are hyaline vascular (70%), characterized by lymphoid follicle proliferation with enlarged blood vessels, while PC-CD and mixed CD are more common in MCD.

The diagnostic challenges of CD arise from its clinical and pathological similarities to other immune and neoplastic diseases, resulting in underestimation and high misdiagnosis rates. CD complications can include paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), kidney injury, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Among these, BO and PNP independently contribute to poor prognosis, with UCD being the most prevalent.

BO, a chronic pulmonary disease resulting from bronchiolar inflammatory injury, manifests as chronic cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. The mortality rate for CD accompanied by BO ranges from 48% to 85%, with a median overall survival time of 3 years. Linear deposition of IgG and complement in bronchial biopsy samples suggests a connection between BO pathophysiology and epithelial autoantibodies generated by CD tumour cells. Immune damage mechanisms, particularly CD8+ T-lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity, may also play a role.

The presented case involved a patient initially treated for pneumonia, ultimately diagnosed with CD accompanied by BO. Surgical tumor removal partially alleviated symptoms, and the patient regained self-sufficiency. Despite the generally poor prognosis, the patient’s long-term use of tripterygium glycosides and prednisone prior to CD diagnosis may have delayed BO progression. Postoperatively, the patient declined glucocorticoid therapy due to concerns about side effects, opting for immunosuppressive medication. Regular follow-ups confirm the patient’s asymptomatic status.

Conclusion: Castleman Disease

While only a few cases of CD with BO have been reported, they highlight the significance of postoperative adjuvant therapy in preventing BO progression. Patients with UCD often undergo complete surgical tumour removal with a favourable 5-year survival rate, but when BO is involved, adjuvant therapy becomes crucial. Existing reports suggest varied outcomes, emphasizing the importance of individualized treatment strategies.

The prognosis for MCD is generally poor, with a risk of transformation into lymphoma or plasmacytoma. Rituximab chemotherapy is the current standard, though long-term efficacy is uncertain due to significant toxicity. Continued research is necessary to refine treatment approaches for CD, especially when complicated by BO.