Acute Coronary Syndrome Due to Saphenous Vein Graft Occlusion One Year After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remains a cornerstone in the management of patients with advanced multivessel coronary artery disease, particularly those with complex anatomy or diabetes mellitus. Despite its proven long-term benefits, graft failure—especially involving saphenous vein grafts (SVGs)—continues to be a major limitation affecting long-term outcomes. This case highlights the presentation, pathophysiology, and clinical implications of acute saphenous vein graft occlusion occurring one year after surgical revascularization and subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

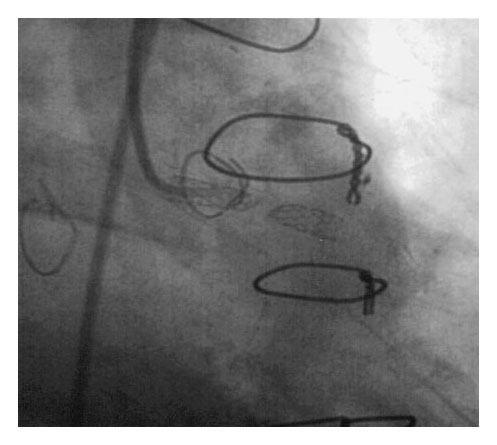

A 57-year-old man presented with several hours of chest discomfort accompanied by ischemic changes on electrocardiography, consistent with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). His medical history was notable for CABG performed one year earlier, followed by PCI with stent deployment in an SVG supplying the first obtuse marginal artery. Coronary angiography revealed severe three-vessel disease of the native coronary arteries, a patent left internal thoracic artery (LITA) graft to the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, a chronically occluded vein graft to the right coronary artery (RCA), and a newly occluded SVG to the first obtuse marginal artery.

This angiographic pattern reflects the well-recognized disparity in long-term patency between arterial and venous bypass conduits.

The LITA–LAD graft is widely regarded as the most durable conduit, with patency rates exceeding 90% at 10 years. In contrast, SVGs are prone to progressive failure, with reported occlusion rates of approximately 15–20% within the first year and nearly 50% by 10 years postoperatively.

The mechanisms underlying SVG failure vary according to the time elapsed since surgery. Early graft failure (within 1 month) is usually due to thrombosis or technical issues. Intermediate failure (1 month to 1 year) is often related to intimal hyperplasia, whereas late failure is driven by accelerated atherosclerosis within the vein graft. In this patient, the occurrence of graft occlusion approximately one year after CABG suggests a transition from intimal hyperplasia to atherothrombotic disease, compounded by prior PCI and stent placement within the graft.

Saphenous vein graft atherosclerosis differs from native coronary artery disease in several important ways. SVG plaques tend to be diffuse, lipid-rich, and friable, making them particularly prone to rupture and distal embolization. These characteristics contribute to a higher risk of periprocedural myocardial infarction and no-reflow phenomena during PCI. Additionally, SVG lesions often progress rapidly despite optimal medical therapy, reflecting the intrinsic vulnerability of venous conduits to arterial pressures and shear stress.

The patient’s presentation with acute ischemic symptoms and electrocardiographic changes underscores the clinical consequences of SVG occlusion. Occlusion of a graft supplying the obtuse marginal artery can result in ischemia of the lateral left ventricular wall, which may manifest as chest pain, ST-segment changes, and hemodynamic instability. In patients with extensive native coronary disease, graft failure may lead to substantial myocardial jeopardy, particularly when alternative sources of collateral flow are limited.

Management of ACS in the setting of SVG occlusion poses unique challenges. Treatment options include PCI of the occluded vein graft, PCI of the native coronary artery supplying the same territory, or, less commonly, repeat CABG. Contemporary guidelines generally favor PCI of the native vessel when feasible, as outcomes are often superior compared with SVG intervention. However, severe diffuse disease of the native arteries, as seen in this patient, may limit this approach.

When SVG PCI is pursued, adjunctive strategies such as distal embolic protection devices are strongly recommended to reduce the risk of microvascular obstruction and periprocedural myocardial infarction. Drug-eluting stents have been shown to reduce restenosis rates compared with bare-metal stents, although they do not eliminate the risk of graft failure. Aggressive secondary prevention—including dual antiplatelet therapy, high-intensity statins, blood pressure control, and lifestyle modification—is essential to slow disease progression.

This case also reinforces the importance of long-term surveillance and risk-factor management following CABG. Patients with vein grafts remain at substantial risk for recurrent ischemic events, even within the first year after surgery. The durability of arterial grafts highlights the evolving preference for multi-arterial revascularization strategies in appropriate patients.

In summary, acute occlusion of a saphenous vein graft is a significant cause of recurrent ischemia after CABG and represents a complex clinical problem with limited durable solutions. Understanding the distinct biology of vein graft disease and applying evidence-based interventional and preventive strategies are critical to improving outcomes in this high-risk population.

References

- Fitzgibbon GM, et al. Coronary bypass graft fate and patient outcome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(5):263–270.

- Goldman S, et al. Saphenous vein graft patency 1 year after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2004;110(11 Suppl 1):II-17–II-22.

- Alexander JH, et al. Effect of ticagrelor on saphenous vein graft patency after coronary artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2439–2447.

- Sabik JF. Understanding saphenous vein graft patency. Circulation. 2011;124(3):273–275.

- Brilakis ES, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in native arteries versus bypass grafts in patients with prior CABG. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(8): 797–804.