A large mass of entangled hair recovered from the stomach of a 16-year-old girl who had normal development and health- A compulsive behavior involving hair-eating!

Presenting Complaint:

A 16-year-old girl presented to the outpatient department with complaints of abdominal pain and vomiting for the past 6 months. The patient reported having frequent bouts of vomiting, which had increased in the last few days before presenting.

History:

The past history of the patient and her family was negative for any psychiatric condition.

Examination:

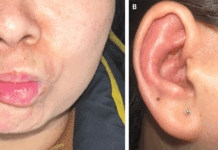

On palpation of the abdomen, there was a mobile mass in the upper abdomen measuring 14 × 16 cm. On palpation, the mass was tender, smooth, and had irregular margins.

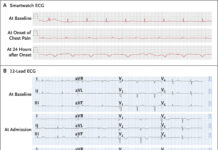

Abdominal ultrasound revealed a strange lesion in the right upper and middle abdomen. The findings were suggestive of gastric bezoars.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, which showed no abnormality in the esophagus, but a large mobile mass of hairs was seen in the stomach.

A working diagnosis of trichobezoar was made. Trichobezoar is a mass in the gastrointestinal tract, made up of mostly hair.

Further Evaluation and Workup:

On further evaluation, it was revealed that the patient had been eating hairs and clay since childhood. She had a strong urge to eat the hairs, so she would ingest the hairs thrown by other family members and would always be in search of more. Moreover, besides eating hair, she also had a strong liking and an urge to eat clay.

The mother of the patient told that she had persistently educated her daughter and even punished her for eating hairs, but the girl would continue doing so. The patient herself denied pulling out her own hair.

On examination of the scalp, the treating healthcare professional didn’t notice any evidence of alopecia or pulling of hair/short hair.

Serological investigations and stool examination were normal.

Management:

The surgeon decided to perform an open laparotomy owing to the size of the mass. The extracted mass was made up of entangled hairs, which confirmed the diagnosis of Pica of childhood (Trichophagia).

Her parents and family were educated and counseled, and so was she. She was educated regarding the consequences of eating hair. Behavioral therapy was provided for urge and impulse control, along with the psychotherapeutic intervention focused on teaching adaptive coping skills to deal with stressful situations, which were the triggers of her trichophagia.

The patient improved after the surgery. At the 6-month follow-up, there were no manifestations suggesting trichophagia or Pica.

References:

Mehra A, Avasthi A, Gupta V, Grover S. Trichophagia along with trichobezoar in the absence of trichotillomania. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5(Suppl 1):S55-S57. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.145204

Tiago S, Nuno M, João A, Carla V, Gonçalo M, Joana N. Trichophagia and trichobezoar: case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:43-45. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010043