Case presentation

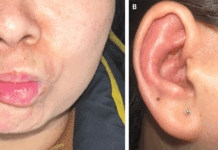

A male Caucasian 16-year-old patient arrived at the emergency room complaining of diffuse myalgia, fever, nausea, and exhaustion that had been present for three days. Along with experiencing dyspnea and two episodes of hemoptysis, he also presented with symptoms of pyrexia and a transcutaneous oxygen saturation of 88% in room air. However, upon examination, he was found to be tachypneic, tachycardic, and free of hemodynamic instability. On pulmonary auscultation, there were bilateral crackles, and abdominal palpation revealed widespread discomfort without rebound or rigidity. The rest of the clinical examination was unremarkable.

Investigation

The bilateral alveolar interstitial syndrome was seen on the chest radiograph. According to laboratory studies conducted upon admission, there were mildly impaired coagulation parameters, such as APTT of 27.3 s (normal range: 20–30 s), INR of 1.10 (normal range: <1.10), PTT of 89% (normal range: 75–100%), fibrinogen of 535 mg/dl (normal range: 200–400 mg/dl), and leukocytosis (8905/μl), thrombopenia (96,000/µl), and lymphopenia (398/μl). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed diffuse alveolar damage and bilateral consolidation. After the patient’s admission, intravenous ceftriaxone was used to start the antibiotic course.

His PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 47, indicating refractory severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, so he needed venous-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (vvECMO) right away. To guarantee lung-protective breathing, airway pressure release ventilation was employed. Fibroscopy inspection revealed a pulmonary hemorrhage, necessitating a large transfusion guided by rotational thromboelastometry. A second CT scan of the chest revealed a substantial rise in pulmonary intraparenchymal lesions, including both lungs completely.

He also had deteriorating coagulation dysfunction, as seen by his platelet counts falling to 25,000/μl, fibrinogen at 153 mg/dl, D-dimer at 20563 ng/ml, INR of 1.19, and APTT of 31.7 s. The patient had conjugated bilirubinemia of 6.7 mg/dl and developed jaundice. Acute renal damage did not occur.

The patient got two units of packed red blood cells, two units of platelets, 77 g of fibrinogen, three units of fresh frozen plasma, and two thousand units of prothrombin, proconvertin, and Stuart factor over seven days.

Upon admission, many tests were carried out, including PCRs, vasculitis screens, and a thorough panel of microbial serologies. Every outcome was negative. On the tenth day of admission, serologies were conducted again, and antibodies against Leptospira were found using a micro-agglutination assay at a titer of 1:1600.

Discussion

According to certain case studies, 85% of patients had lung involvement in leptospirosis, which is a common occurrence. Hematological characteristics that are linked to clinical bleeding, particularly pulmonary bleeding, are also common. These characteristics include thrombocytopenia and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

It is unclear what physiopathology underlies the coagulopathy in the leptospirosis setting. However, recent research indicates that Leptospira and its toxins cause vascular leakage, loss of vascular integrity, and multiorgan failure by acting on endothelial cell surface receptors. Although severe hypofibrinogenemia, such as that seen in our patient, has not yet been documented, it has been advised to keep fibrinogen levels above 1 g/l in hemorrhagic situations.

The increased death rate can be attributed to bleeding diseases and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.

In cases of severe leptospirosis, the use of additional therapies such as corticosteroid therapy and plasmapheresis has been documented. However, no discernible advantage has been seen when comparing these therapies to conventional antibiotic therapy. An early start to antibiotherapy is connected with better outcomes.

Direct inspection, culture, and PCR can all be used for bacterial detection; however, isolating the organism is difficult. Antibody titers against Leptospira are measured using serological tests; however, the assays’ applicability varies according to the infection time. IgM antibodies start to show up five to seven days after infection. The results of the microscopic agglutination test are 63% and 97%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay are 89% and 94%, respectively. It is sufficient to confirm an ongoing or recent infection with a single titer > 1:800.