Case study: an unusual presentation of Actinomucor elegans infection

This article describes an unusual case of mucormycosis caused by Actinomucor elegans. The condition has a high mortality rate, especially in immunocompromised patients and can be difficult to identify via conventional methods. Similarly, because of the morbid and progressive nature of the disease, early diagnosis is essential for the effective management of the disease. In a similar case, a 70-year-old male patient with a history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and diabetes mellitus presented with a large nasal septal black eschar that rapidly developed during tooth extraction. The patient further had a history of nosebleeds, falls, recent weakness and tooth pain. Earlier, he had been treated for MDS with decitabine therapy. And at the time of presentation, he was on azacytidine (VIDZA).

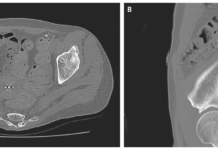

On admission, the patient was hyperglycemic, and doctors started him on an insulin drip. He was further referred for an X-ray of the mandible, which showed a periapical abscess at the root of the second molar, including a large carious lesion in the left mandibular molar with carious erosion of the crown. The patient’s teeth were extracted on the morning of the admission.

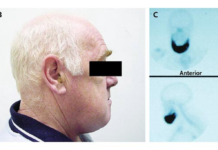

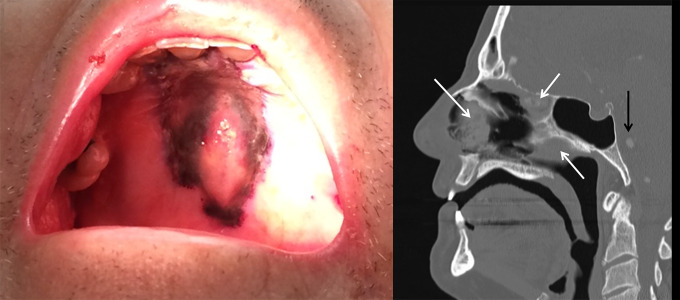

However, the patient had been in pain for several months and dental care of delayed because of chemotherapy-induced leukocytosis. While the patient’s tooth was being extracted, a black eschar appeared on the hard palate. Although the lesion was not draining, it was tender on palpation and increased in size while the procedure was ongoing. During the procedure, right periorbital swelling also developed.

Diagnosis and prognosis

Doctors immediately performed a fungal smear which showed pauciseptate hyphae, consistent with zygomycete and budding yeast. Doctors started the patient on liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole and micafungin. Similarly, the patient was advised an MRI with contrast which was significant for invasive fungal rhino-orbital sinusitis and disseminated multifocal mycotic emboli in the brain. Fungal culture identified Candida albicans. However, this was not thought to be contributing to the disease and is a common colonizer of the nose. On the 3rd day, a cottony mold with abundant aerial hyphae developed, filling the plate by the 5th day. The mold was subcultured on the 3rd day for promoting spore production. Further analysis via MALDI/TOF and Sanger sequencing identified the growth of Actinomucor species. The findings were consistent with the diagnosis of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis.

Treatment includes extensive surgery with enucleation and removal of the nose/maxilla in association with antifungal therapy. However, the survival rate in patients with disseminated disease is only 5%. In this case, the patient did not show any improvement with antifungals alone and because of the poor prognosis of mucormycosis and the patient’s poor immunity, the family decided to transfer the 70-year-old to comfort care.

The patient died an hour later, 14 days after his initial presentation of nosebleeds and 8 days since the tooth extraction and hospitalization.

Source: NCBI