A non-profit organization contacted a paediatric surgeon to evaluate the possibility of surgical separation of conjoined twin girls. The twins were born in East Africa by spontaneous vaginal delivery. The family was advised to see surgical opinion in the United States because of the anticipated marked complexity of separation.

Arrangements were made for the children to receive care at a hospital in the US through the outreach efforts of a non-profit organization. The family travelled to Boston when the girls were 22 months of age. The twins were seen at the paediatric surgery clinic at the hospital on arrival.

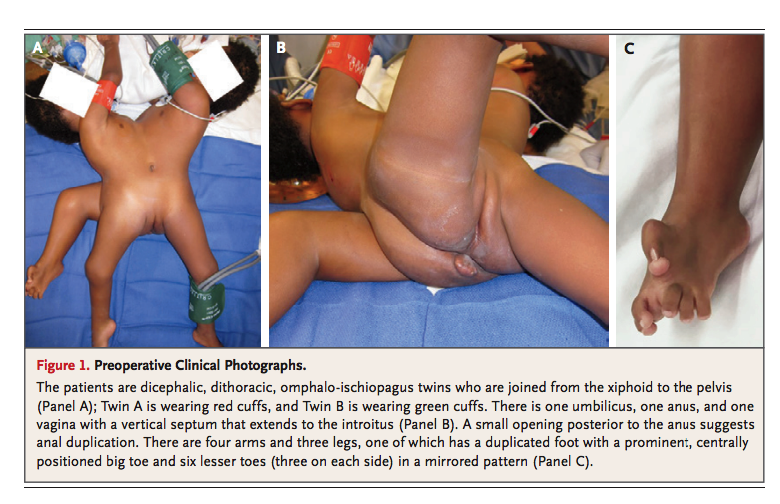

On physical examination, the twins were noted to be joined from the xiphoid to the pelvis, omiphaloischiopagus, dithoracic and dicephalic. The twins when facing each other, were unable to remain or stand in a recumbent position. Twin B was more interactive, vigorous, alert and larger, whereas, Twin A was more difficult to engage and was less active. The twins shared a vagina with a vertical septum that extended to the introitus, anus and umbilicus. Posterior to the anus, the twins had a small opening that suggested anal duplication. The twins had four arms and three legs, six lesser toes in a mirrored fashion, a centrally positioned and prominent big toe.

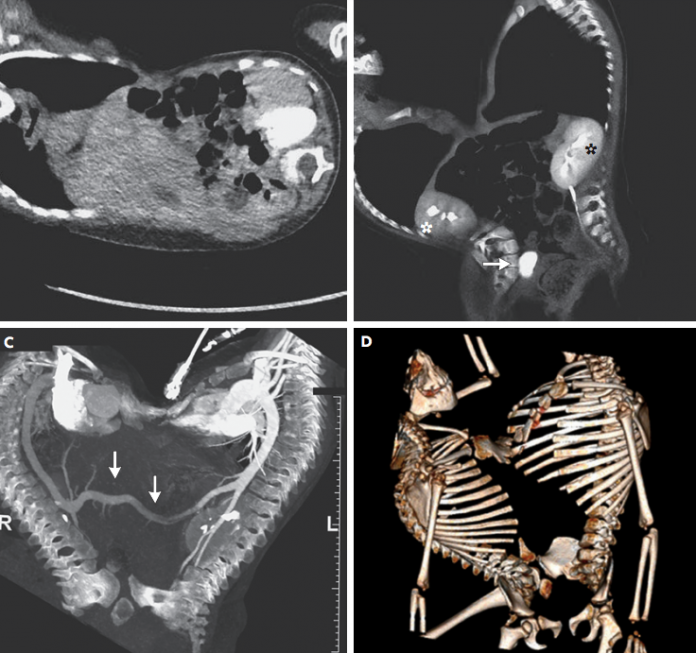

Imaging studies were performed to further define the anatomy of the twins. Computed tomography of the pelvis, abdomen and thorax was performed using an electrocardiogram gated, high-pitch protocol for assessment of osseous anatomy, visceral organ and cardiovascular anatomy. CT revealed a single liver that spanned the shared abdominal cavity of the twins. Each of the twins had a smaller dysplastic kidney and one dominant kidney with a ureter draining into a shared bladder in the pelvis. The GI tracts were fused partially whereas, Twin B had an anatomically complete pelvis.

Case outcome

The ethics committee relied heavily on insights of the cardiology team to understand the probable outcomes. Twin A was dying, imminently. She suffered from severe hypoxemic events and recurrent pneumonia.

According to the author of a study ‘Surgery for conjoined twins’, “Where one twin is dead or has a lethal abnormality and cannot survive independently from its normal twin and if unoperated both twins would die, separation to save the healthy twin should be attempted.”

In this particular case, the surgical team thought that they had the technical expertise for performing the surgical procedure, however, there was no guarantee for the survival of Twin B, given the conjoined circulation.

References

Cummings, B. M., Gee, M. S., Benavidez, O. J., Shank, E. S., Bojovic, B., Raskin, K. A., & Goldstein, A. M. (2017). Case 33-2017: 22-Month-Old Conjoined Twins. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(17), 1667-1677.

Spitz, L. (2003). Surgery for conjoined twins. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 85(4), 230.