An 83-year-old woman came to the gastroenterology clinic with complaints of difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and regurgitation with each meal. The patient also complained of chest pain after food intake (postprandial chest pain).

The patient had a history of dysphagia for both solids and liquids for the past couple of years. The symptoms had exaggerated in the previous year with a weight loss of 9 kgs in a year.

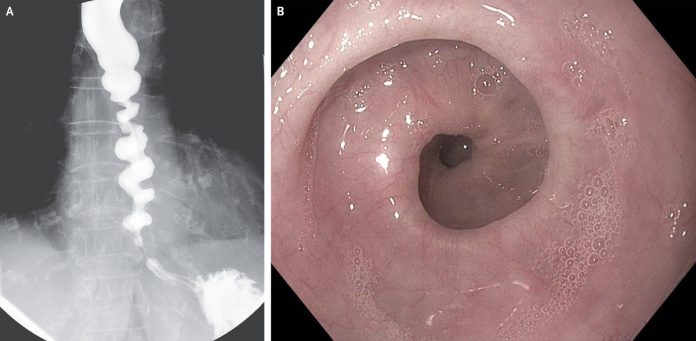

A corkscrew pattern was seen on barium esophagram (Panel A). Esophagoscopy revealed tight gastroesophageal junction and nonperistaltic spastic contractions (Panel B).

Esophageal manometry showed an increased relaxation pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter, absence of peristalsis, and spastic contractions consistent with spastic achalasia.

The patient was offered endoscopic myotomy, but she declined. Instead, her achalasia was managed with endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin. At a 5-month follow-up, her symptoms had reduced substantially with no regurgitation and only intermittent dysphagia.

Achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder.

In simpler words, when the food pipe fails to push the food to the stomach due to defective contractions and relaxations (peristalsis) of the esophagus and due to impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. These abnormalities create a functional blockage in the passage of the food, thus dysphagia.

Achalasia is a rare disorder

that can, though, affect any age, but it is mostly seen in individuals between

20 and 60 years. Children are usually spared.

Less than 5% of cases have been reported in children.

Symptoms of achalasia develop insidiously and include gradually progressive dysphagia to both solids and liquids. Other clinical manifestations include regurgitation of undigested food, mild to moderate weight loss, chest pain, indigestion, etc.

Chest pain may occur either postprandially or spontaneously. Regurgitation is a potential health hazard, particularly if nocturnal, as it may lead to pulmonary aspiration. Another important concern is weight loss. Severe weight loss is a red flag, especially in the elderly, and when coupled with rapidly progressive dysphagia, as it can be a sign of cancerous growth presenting as achalasia.

Esophageal manometry is the gold standard investigation for achalasia.

The classical features of achalasia seen on manometry are

- Increased resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure

- Impaired relaxation of the LES in response to swallowing

- Absence of peristalsis

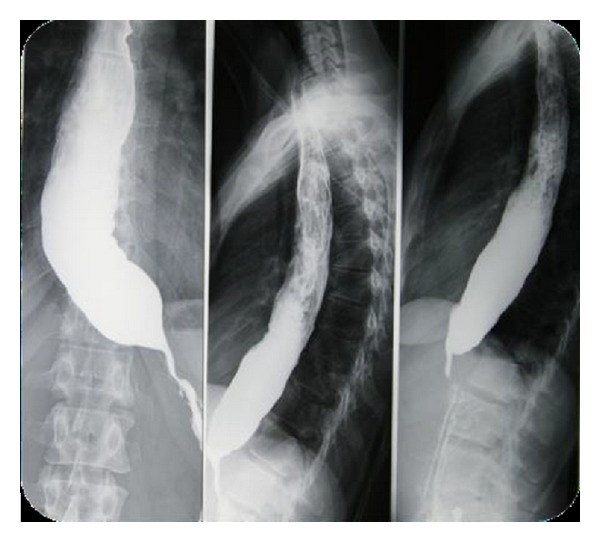

Other investigation options include a barium swallow and endoscopy.

Barium swallow shows characteristic bird beak appearance of the lower esophagus. Also, it reveals a dilated esophagus, and the contrast material takes more time than usual to pass through the esophagus because of impaired LES relaxation.

Management options include

- Graded Pneumatic dilation

- Laparoscopic myotomy

- Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin injection to block acetylcholine at LES

- Medical treatment with calcium channel blockers or nitrates to relax the LES. This option is the least helpful and only suitable for elderly patients who can’t undergo any other treatment methods.

The bottom line to diagnose achalasia in time and select an individualized management approach as directed by the patient’s age, symptomatology, and comorbidities.

References

Kristle Lee Lynch, M. P. (2019, July). Achalasia. Retrieved from MSD Manual: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/esophageal-and-swallowing-disorders/achalasia

Samuel Han, M. a. (2020, April 30). Corkscrew Esophagus in Achalasia. Retrieved from The New England Journal of Medicine: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm1911516

Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Aug. 108(8):1238-49; quiz 1250.